Saul told his son Jonathan and all the attendants to kill David.

1 Samuel 19:1-10

But Jonathan had taken a great liking to David and warned him,

“My father Saul is looking for a chance to kill you. Be on your guard tomorrow morning; go into hiding and stay there.

I will go out and stand with my father in the field where you are. I’ll speak to him about you and will tell you what I find out.”

Jonathan spoke well of David to Saul his father and said to him,

“The king should not do wrong to his servant David;

he has not wronged you,

and in fact what he has done has helped you greatly.

He took his life in his hands when he killed the Philistine. The Lord won a great victory for all Israel, and you saw it and were glad. Why then would you do wrong to an innocent man like David by killing him for no reason?”

Saul listened to Jonathan and took this oath:

“As surely as the Lord lives, David will not be put to death.”

So Jonathan called David and told him the whole conversation. He brought him to Saul, and David was with Saul as before.

Once more war broke out, and David went out and fought the Philistines. He struck them with such force that they fled before him.

But an evil spirit from the Lord came on Saul as he was sitting in his house with his spear in his hand.

While David was playing the lyre,

Saul tried to pin him to the wall with his spear,

but David eluded him as Saul drove the spear into the wall.

That night David made good his escape.

Maybe it is just me, but somehow I think I am probably not the only one who has been feeling as though these last few months have been marked by a great deal of loss.

I have watched as so many in my church community have carried their grief—grief over the suffering of loved ones and neighbors and how their losses impact our own lives, despair for a world reeling from conflict and violence with barely a moment to catch our breath, sorrow for the many innocent people who have had their lives devastated by hurricanes and other natural disasters that have been made worse by climate change.

This week, so many friends, neighbors, and church family have carried a tender grief for one of our own as they comprehend a world without their beloved child, who died at the age of 16 in a car accident last week. They have cried their tears. They have offered meals. They have shared their own stories with each other, sorrow over children that they have buried too soon. Their wounds are deep. Their wounds are real.

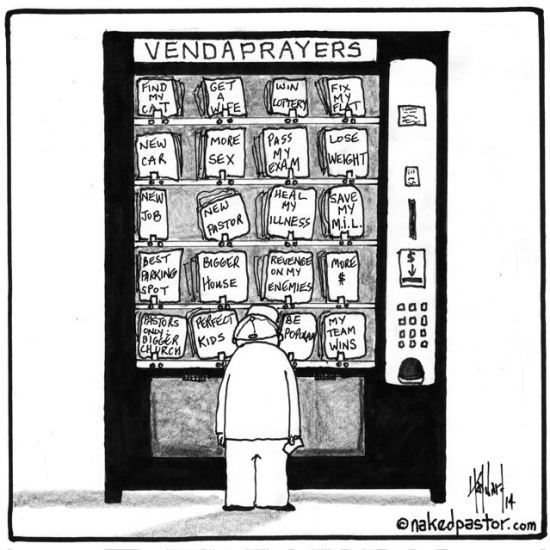

In a world where we can, and often are, wounded, it can be easy to live out of our fear. To draw into ourselves. To see dangers around every corner. To let fear animate not just our words but our actions. The poet Hafez once wrote that “fear is the cheapest room in the house,” and I think he was on to something there. Because fear is the easiest place to find ourselves. It doesn’t require much imagination at all. And it is an awful emotion to live our lives from.

Now, King Saul knew a thing or two about fear. That should be clear enough from our Scripture lessons today. Right on the heels of David’s victory over Goliath, Saul has taken the young champion into his care, and has watched as his own son has “become one in spirit” with David. He has observed as David has risen in stature despite everything that should work against him as a pretty boy from nowhere and the youngest of seven sons. He has listened as the city has fallen in love with David. David, who has slain tens of thousands. David, whom his own son loves more than himself. David, to whom everything seems to come so easily.

Friends, Saul is afraid.

I think back to the times in my life when I have felt insecure in myself, when I have worried that the person that I am is not enough. It is such an awful, isolating feeling, isn’t it? To doubt your own worth? To worry that the people with whom you share your life are just looking for a reason to walk away? When I remember myself in those moments, I can have compassion for Saul. He truly seems alone here—yes, he is the king, but the story he is telling himself, and the story that scripture seems to be telling us, is that everyone has abandoned him for David. There is nothing more awful than being scared and alone. And there is little that is more dangerous than a powerful person who is scared and alone.

Our own history can be a helpful teacher here. January of 1933 was a similar moment in Germany. This was shortly before Hitler came to power, and in Berlin unease was widespread. Speaking to his own congregation in a moment of great fear, Dietrich Bonhoeffer reflected

“the overcoming of fear—that is what we are proclaiming here (point at sanctuary). The Bible, the gospel, Christ, the church, the faith—all are one great battle cry against fear in the lives of human beings. Fear is, somehow or other, the archenemy itself. It crouches in people’s hearts. It hollows out their insides, until their resistance and strength are spent and they suddenly break down. Fear secretly gnaws and eats away at all the ties that bind a person to God and to others, and when in a time of need that person reaches for those ties and clings to them, they break and the individual sinks back into himself or herself, helpless and despairing, while hell rejoices.”[1]

Bonhoeffer, Dietrich. “Overcoming Fear,”

Fear tells us that we are alone in our suffering. It tells us that nobody will help us. Nobody will save us. So perhaps it shouldn’t surprise us that, in our fear, we tend to make awful decisions. Like Saul, we resort to violence, we lash out at the people around us. Fear takes away our humanity.

So what is the alternative?

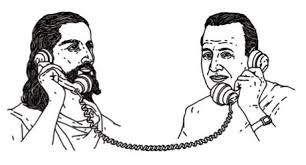

That is the question. And one answer, I think, is sitting in these pews with us every Sunday and is gathered around the table every time we choose fellowship over going it alone. You see, if fear tends to eat away at the ties that bind us to God and to others, then perhaps the antidote to fear is the hope that we encounter when we choose to be in community with others. It is what happens when we struggle against the temptation to turn inward, and instead look for strength in one another. In our Scripture this morning, David could not withstand Saul’s fear on his own—he is able to negotiate this incredibly awful situation with Saul because of his friendship with Jonathan. With a friend at his side, David is literally able to dodge the slings and arrows of death. Friendship is what saves him.

Perhaps this seems too simple, and yet remember: the God who came to us in Christ, who told us to not be afraid, offers us the gift of fellowship and friendship over and over again:

- Come to me, all you who are weak and heaven laden, and I will give you rest.

- Fear not, for I am with you.

- Let not your hearts be troubled, neither let them be afraid.

Perhaps you believe that there might be something better than living only for yourself, worried only about your own difficulties and concerns. Perhaps you are tired, so tired of carrying your fears and disappointments, your anxiety and the hurts that can become like a heavy yoke, holding you down. Perhaps you are weary of trying to fight your fears alone.

We seek out one another, I think, because we know that God desires for us something better than a life lived in fear. We come to worship because perhaps we believe the church can help us to live differently. That somehow, when we gather together, when we lift our voices as one to the Creator who made us and called us by name, we will find a strength that we didn’t know was in us to withstand the fears of this time. And that when we cannot find that strength in ourselves, others will be there to hold us and to whisper words of hope on our behalf until we are strong enough. In worship, if we are lucky, we encounter the great affirmation of a God who loves us, and gathers us together and bids us banish fear, not just for ourselves, but for the sake of a world that is crying out for healing.

So let us lean deeply into that hope when we have the strength to do so. And let us trust one another to hold fast to us when we are broken with sorrow. Let us live out a faith that is wide and broad enough to hold the fears of this world, and to answer that fear with the persistent hope found in a God who gathers the brokenhearted together and calls us friend, neighbor, beloved.

[1] Bonhoeffer, Dietrich. “Overcoming Fear,” https://politicaltheology.com/overcoming-fear-sermon-dietrich-bonhoeffer/

But fortunately for us, Moses learns that no hideout is so distant that God cannot find you. In the land of Ur, far from any Egyptian or Israelite, God reveals himself to Moses. And in a moment of brilliance, the light of God shines upon this wandering child of God and reveals to him a third way, a new opportunity to bear witness to God’s justice in the face of a dark dark world.

But fortunately for us, Moses learns that no hideout is so distant that God cannot find you. In the land of Ur, far from any Egyptian or Israelite, God reveals himself to Moses. And in a moment of brilliance, the light of God shines upon this wandering child of God and reveals to him a third way, a new opportunity to bear witness to God’s justice in the face of a dark dark world.