1 JOHN 3:16-24

16We know love by this, that he laid down his life for us — and we ought to lay down our lives for one another. 17How does God’s love abide in anyone who has the world’s goods and sees a brother or sister in need and yet refuses help?

18Little children, let us love, not in word or speech, but in truth and action. 19And by this we will know that we are from the truth and will reassure our hearts before him 20whenever our hearts condemn us; for God is greater than our hearts, and he knows everything. 21Beloved, if our hearts do not condemn us, we have boldness before God; 22and we receive from him whatever we ask, because we obey his commandments and do what pleases him.

23And this is his commandment, that we should believe in the name of his Son Jesus Christ and love one another, just as he has commanded us. 24All who obey his commandments abide in him, and he abides in them. And by this we know that he abides in us, by the Spirit that he has given us.

GOSPEL JOHN 10:11-18

11“I am the good shepherd. The good shepherd lays down his life for the sheep. 12The hired hand, who is not the shepherd and does not own the sheep, sees the wolf coming and leaves the sheep and runs away — and the wolf snatches them and scatters them. 13The hired hand runs away because a hired hand does not care for the sheep. 14I am the good shepherd. I know my own and my own know me, 15just as the Father knows me and I know the Father. And I lay down my life for the sheep. 16I have other sheep that do not belong to this fold. I must bring them also, and they will listen to my voice. So there will be one flock, one shepherd. 17For this reason the Father loves me, because I lay down my life in order to take it up again. 18No one takes it from me, but I lay it down of my own accord. I have power to lay it down, and I have power to take it up again. I have received this command from my Father.”

The devout cowboy lost his favorite Bible while he was mending fences out on the range. Three weeks later, a sheep walked up to him carrying the Bible in its mouth. The cowboy couldn’t believe his eyes. He took the precious book out of the sheep’s mouth, raised his eyes heavenward and exclaimed, “It’s a miracle!” “Not really,” said the sheep. “Your name is written inside the cover.”

The traditional view of sheep tends to be that they are dumb. People seem to think they are just wool-machines and walking leg roasts. Which they are.

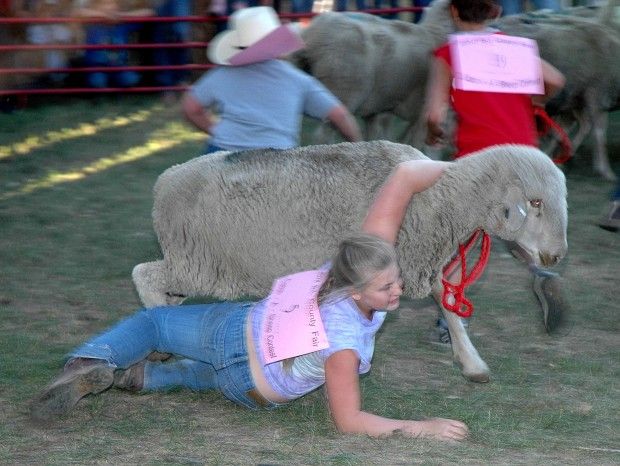

The truth is that sheep aren’t the smartest animals in the world, but they are pretty wise. I should know; I grew up chasin’ em. They have almost a natural instinct of self-preservation. They can sense, for example, when a young person is trying to sneak up on them and grab them. They can also drag that young person up a hill when she manages to get hold of a hoof and not much else.

Story by a journalist named Steve Carrier about the time that he and his brother tried to run down some Bighorn sheep and quickly realized they were being played by the animals. His brother was a scientist and was an early adopter of the theory that ancient humans were persistence hunters, which means that they would chase their prey until it dropped to the ground with exhaustion. Scott and his brother went out to Colorado to chase Bighorn sheep, and after a couple of days realized that the sheep were, well, smarter than them. The literally ran loops around Scott and his brother, and frequently disappeared into larger herds to confuse them. Needless to say, the sheep won.

The problem with sheep is that sometimes they get carried away in the heat of their emotions. They get afraid, their adrenaline gets going, and they can find themselves separated from the herd. And that is when a sheep gets in trouble. You see, in a herd, sheep can work together to protect themselves. There is power in numbers. But when they are alone, they are completely exposed, and they know it. One of the most awful sounds in the world is the sound of a terrified sheep.

Now, in our Scripture this morning Jesus uses the metaphor of the Shepherd and his Sheep to describe the relationship between God and us. It probably isn’t surprising—Jesus lived in a rural culture, one where people were very familiar with shepherds and shepherding. Many people believed that the Messiah, when he came, would be a Shepherd who tended the flock of Israel like David.

Jesus, I think, is onto something slightly different here. When Jesus speaks of the shepherd and the sheep in John 10, he wants us to know that ours is the kind of God who will not leave us out in the cold—that when we find ourselves alone, forsaken, terrified—at the same time God is out there seeking us out, gathering us in, connecting us to other souls so that we don’t have to journey alone.

In this way, God embodies the work of 1 John, the task of “loving” one another that is so crucial to the Christian life.

There it is, Love. Love is one of those things that can be hard to describe. We all know eros, or romantic love. But what about the brotherly love, or agape, that the bible so often speaks of? What does that look like?

For Jesus, agape looks like a shepherd who tends his flock and who seeks out the lost sheep. In other words, it’s sort of like that famous line from Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart- “I know it when I see it.”

So what does it look like for us, then? According to 1 John, “Little children, let us love, not in word or speech, but in truth and action.”

Love looks like a verb. It looks like the work we do every day to choose connection over isolation, justice over selfishness, and peace over chaos. And all of those actions, small and large, come together to keep us together in one big community, one faithful flock. Or, as well like to call it, the church.

Love looks like a verb. It looks like the work we do every day to choose connection over isolation, justice over selfishness, and peace over chaos. And all of those actions, small and large, come together to keep us together in one big community, one faithful flock. Or, as well like to call it, the church.

Let me give you an example of what love might look like. In the 1980s, my dad had just bought his dental practice in the Bay Area. Just as he was beginning to build relationships with his patients, people started dying. Turned out that the Bay Area was ground zero for a deadly disease called AIDS. No one knew how it was spreading, but everyone knew it was a death sentence. Many medical professionals like my father rightly worried that they might put themselves and others at risk by treating HIV positive patients.

Many doctors and dentists turned these patients away out of fear. But not my dad. He was afraid, but he was unwilling to let fear tear apart his relationships to his patients. So he continued to see and treat AIDS patients. He never turned one away.

The good news about love is that it doesn’t require that we have it all figured out. You can love without understanding exactly what it means. You can love without being certain.

In fact, according to the scriptures, the very act of doing helps us understand. Loving forms us into a community that “knows it when we see it.”

Today we have had the incredible blessing of welcoming new beloved children of God into our fellowship. We have gathered together, chosen community over going it alone. And those who have joined us yearn to get to the task of loving. Over the past few months, they have shared with me their hunger for meaning, their joy at being able to make a difference. Together, they represent a passion for justice, and kindness, and compassion, and they believe that this community is where they have been called to love more fully. And they have chosen you to be their flock.

So I have a wild proposal. Let’s take them up on their offer. Let’s be the kind of church that practices love, even though we don’t have all the answers. And let us not minimize love, or confine it to some tidy box. Let’s make it more than just liking ourselves. Let’s make it more than how wonderfully welcoming we are inside these walls. Let’s let love out of the box and see what it does out in the world. Because at the end of the day, that is the point, isn’t it?

“Little children, let us love, not in word or speech, but in truth and action.” That is the Gospel right there. So let’s get to it.

Are you looking for new ways to worship during Holy Week? Tired of all those services, and candles, and scripture readings? Join us for the inaugural DISCIPLE DASH 5k! Come work off your Agape Meal as you run in terror from the authorities and the Roman guards. Join your fellow disciples in a race from your life that willtake you as far from Jesus as you can manage. But watch out! Jesus might just end up finding you as you run! Avoid the guards and your suffering Lord, and be the first to hide in a dark upper room! Top finishers will receive thirty silver coins, a healthy dose of hopelessness, and unrelenting guilt and shame.

Are you looking for new ways to worship during Holy Week? Tired of all those services, and candles, and scripture readings? Join us for the inaugural DISCIPLE DASH 5k! Come work off your Agape Meal as you run in terror from the authorities and the Roman guards. Join your fellow disciples in a race from your life that willtake you as far from Jesus as you can manage. But watch out! Jesus might just end up finding you as you run! Avoid the guards and your suffering Lord, and be the first to hide in a dark upper room! Top finishers will receive thirty silver coins, a healthy dose of hopelessness, and unrelenting guilt and shame.